MXB-DU Oilless Bearing SF-1 Bushing High-Temperature Resistance

Cat:Oilless Bearing

SF stands for three-layer composite, namely steel plate layer, copper powder layer and plastic layer. The steel plate layer plays the role of assembly...

See DetailsContent

In the demanding world of mechanical engineering, where extreme temperatures, vacuum conditions, and maintenance-free operation are paramount, solid-lubricating bearings emerge as a critical engineering solution. Unlike conventional bearings that rely on oils or greases, these advanced components utilize inherently lubricious solid materials integrated directly into their structure to provide reliable, long-lasting performance where liquid lubricants would fail, degrade, or contaminate. From the frigid vacuum of space to the scorching heat of industrial furnaces, solid-lubricating bearings enable motion in some of the most hostile environments imaginable. This comprehensive guide explores the materials, mechanisms, types, and applications of this vital technology, providing engineers and designers with the knowledge to specify and utilize these bearings effectively.

A solid-lubricating bearing (often called a self-lubricating or dry-bearing) is a mechanical component designed to allow relative motion between surfaces while minimizing friction and wear without the need for a continuous supply of liquid or grease lubricant.

Core Working Principle:

The bearing operates by transferring a thin, continuous film of solid lubricant from the bearing material onto the surface of the mating shaft (the journal). This transfer film acts as a sacrificial layer, preventing direct metal-to-metal contact. As the bearing wears slightly during initial run-in and operation, fresh solid lubricant is continuously exposed or replenished from the composite matrix, maintaining the protective film for the life of the bearing. This mechanism provides consistent, low-friction performance.

The performance of the bearing is defined by the solid lubricant used. Each has unique properties suited to specific environments.

Graphite: One of the most common solid lubricants. Its layered lattice structure provides low shear strength. It offers excellent performance in air and at moderate temperatures (up to ~450°C in air). However, its lubricity diminishes in vacuum or dry inert gases, as adsorbed gases and moisture are necessary for its effectiveness.

Molybdenum Disulfide (MoS₂): Known as "moly," this is the premier lubricant for vacuum and space applications. Its layered sulfide structure provides superb lubricity in the absence of oxygen and moisture. It performs well from cryogenic temperatures up to about 350°C in vacuum, but can oxidize and degrade in moist, oxygen-rich air at high temperatures.

Polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE): Offers the lowest coefficient of friction of any known solid lubricant. It is chemically inert and effective from cryogenic temperatures up to about 260°C. Its main limitations are low mechanical strength, high cold flow (creep), and poor thermal conductivity. It is often used as a composite or as a filler in other materials.

Other Advanced Materials:

Soft Metals (Lead, Gold, Silver, Indium): Used as thin films or alloy constituents, they shear easily and are effective in vacuum and radiation environments.

Graphite Fluoride & WS₂: Advanced variants offering higher temperature stability or alternative environmental compatibility.

Polymer-Based Composites: Materials like PI (Polyimide) and PEEK (Polyether Ether Ketone) are often impregnated with PTFE, graphite, or other lubricants to create high-performance, wear-resistant polymer bearings.

Solid-lubricating bearings are not a single material but an engineered system. Common designs include:

Sintered Metal Matrix Bearings:

Structure: Powdered metal (typically bronze, iron, or steel) is sintered to create a porous matrix. This porous structure is then vacuum-impregnated with a solid lubricant, often a PTFE-based or MoS₂-based blend, and sometimes additional fillers like lead.

Advantages: Good load capacity, excellent wear life, and ability to hold additional lubricant in pores. The metal backing provides structural strength and good thermal conductivity.

Applications: Automotive components, appliances, industrial machinery.

Woven Fiber Reinforced Composites:

Structure: A fabric liner (often PTFE fibers interwoven with high-strength fibers like glass, carbon, or aramid) is bonded to a metal backing (steel or aluminum). The PTFE fibers provide lubricity, while the reinforcing fibers provide strength and wear resistance.

Advantages: Extremely high PV (Pressure-Velocity) limits, excellent impact resistance, and tolerance for misalignment and debris. Can run completely dry or with minimal initial lubrication.

Applications: Aerospace control surfaces, hydraulic cylinder mounts, heavily loaded linkages.

Polymer-Based Composite Bearings:

Structure: Engineering polymers (PTFE, PI, PEEK, Nylon) are compounded with reinforcing fibers (glass, carbon, aramid) and solid lubricant fillers (graphite, MoS₂, PTFE powder).

Advantages: Lightweight, corrosion-resistant, quiet operation, and capable of running submerged in water or other fluids.

Applications: Food processing machinery, medical equipment, marine applications, cleanrooms.

Sputtered or Burnished Coatings:

Structure: Thin films (a few microns) of MoS₂, PTFE, or soft metals are applied via physical vapor deposition (PVD) or simple burnishing onto precision bearing surfaces (e.g., ball bearings or roller bearings).

Advantages: Provides lubrication for precision components in vacuum or extreme environments without changing clearances.

Applications: Spacecraft mechanisms, satellite instruments, vacuum chamber robotics.

Advantages:

Maintenance-Free Operation: Eliminates the need for lubrication schedules, reducing lifecycle costs and enabling use in sealed or inaccessible locations.

Extreme Environment Capability: Operate reliably in high vacuum, extreme temperatures (cryogenic to over 300°C), and under high radiation.

Contamination-Free: No grease to drip, leak, or attract dust. Essential for cleanrooms, food, pharmaceutical, and semiconductor manufacturing.

Simplified Design: No need for complex lubrication systems (oil lines, pumps, reservoirs), seals, or grease fittings.

Limitations & Design Considerations:

Higher Initial Friction: Coefficient of friction is generally higher than a fully lubricated hydrodynamic oil film.

Heat Management: Solid lubricants have lower thermal conductivity than metals. Heat generated by friction must be carefully managed through design, material selection, or external cooling in high-PV applications.

Limited Wear Life: Unlike an oil-lubricated bearing with a continuous supply, solid-lubricating bearings have a finite lubricant reservoir. Life is predictable based on PV calculations but is ultimately limited.

Sensitivity to Certain Environments: Performance can degrade in specific atmospheres (e.g., graphite in dry vacuum, MoS₂ in humid, oxidizing air at high temperature).

Solid-lubricating bearings are indispensable in sectors where conventional lubrication is impossible or undesirable.

Aerospace & Defense: Control surface linkages, landing gear components, missile actuators, and helicopter rotor systems where reliability and extreme temperature tolerance are critical.

Space Technology: The quintessential application. Used in satellite solar array drives, antenna pointing mechanisms, and deployment actuators operating in the hard vacuum and temperature extremes of space.

Vacuum and Semiconductor Manufacturing: Robotics, wafer handling arms, and valve actuators within vacuum chambers where outgassing from oils would contaminate the process.

Food, Beverage & Pharmaceutical Processing: Conveyors, packaging machines, and valves where grease contamination poses a health risk and frequent washdowns would degrade liquid lubricants.

Automotive: Components in areas prone to grease washout (suspension joints, pedal assemblies) or high-temperature zones.

Cryogenic Systems: Valves and actuators in liquid nitrogen or helium systems where lubricants would solidify.

Selecting the optimal bearing requires a systematic analysis of the operating conditions. Use this framework:

1. Define the Operating Environment (THE MOST CRITICAL STEP):

Temperature Range: What are the min/max operating temperatures?

Atmosphere: Vacuum, dry air, humid air, inert gas, underwater?

Contamination Sensitivity: Is the area a cleanroom, or is debris ingestion a concern?

Chemical Exposure: Will it be exposed to solvents, acids, or alkalis?

2. Analyze Mechanical Loads and Motion:

Load (P): Static, dynamic, and shock loads in MPa or psi.

Velocity (V): Sliding speed in m/s or ft/min.

PV Value: The product of Pressure and Velocity is the key design parameter. Ensure the selected bearing material's maximum rated PV exceeds your calculated operating PV.

Motion Type: Continuous rotation, oscillation, or linear motion? Oscillatory motion is often more challenging for film formation.

3. Material Selection Matrix based on Primary Driver:

| Primary Requirement | Recommended Bearing Type / Lubricant | Key Reason |

|---|---|---|

| Ultra-High Vacuum | Sputtered MoS₂ coating; MoS₂-impregnated composite | MoS₂ provides stable, low outgassing lubricity in vacuum. |

| High Temperature (in Air) | Graphite-based metal matrix; Specialized PI composites | Graphite retains lubricity at high temperatures in air. |

| Very High Load & Shock | Woven PTFE fabric composite (e.g., filament wound) | High strength fibers (aramid/glass) provide exceptional load capacity and toughness. |

| Corrosion Resistance / Wet | Polymer composite (PEEK, PVDF, Nylon with PTFE) | Inert polymers resist chemicals and can run submerged. |

| Low Friction, Dry | PTFE-rich composite or thin film | PTFE has the lowest inherent coefficient of friction. |

| Precision & Low Torque | Sputtered soft metal (Au, Ag) or thin PTFE film on ball bearings | Provides precise lubrication without affecting tolerances. |

4. Consider Installation and Housing Design:

Ensure proper interference fit for sleeve bearings to maintain thermal contact and prevent rotation. Provide adequate clearance for thermal expansion. Housing material should have a higher thermal expansion coefficient than the bearing liner to maintain fit at temperature.

Installation: Handle with clean tools to avoid contaminating the bearing surface. Do not wash or degrease (unless specified). Press fit using arbor presses—never hammer directly on the bearing liner.

Run-In: A brief run-in period under moderate load helps establish a smooth, uniform transfer film on the shaft.

Lifespan Prediction: Bearing life is primarily a function of wear rate, which depends on the operating PV, temperature, and environment. Manufacturers provide wear rate data (e.g., μm/hr per unit of PV) to calculate theoretical linear wear and predict service life.

Inspection: Monitor for increased friction, play, or unusual noise. Inspect the shaft for scoring or loss of the characteristic dark transfer film.

Research is pushing the boundaries of performance and intelligence:

Nanostructured Lubricants: The use of nanotubes (BN, MoS₂), graphene, and nano-particle additives to create ultra-durable, low-friction composite films with exceptional properties.

Adaptive & Smart Materials: Development of chameleon coatings that can adapt their surface chemistry in real-time to changing environments (e.g., forming a protective oxide at high temperature that then acts as a lubricant).

Advanced Manufacturing: Additive manufacturing (3D printing) of complex, integrated bearing structures with graded material properties, optimizing lubricant distribution and structural strength in a single component.

Solid-lubricating bearings represent a triumph of materials science over some of engineering's most severe constraints. They are not a universal replacement for oil-lubricated bearings but a specialized, enabling technology for applications where conventional lubrication is a liability. Success hinges on a deep understanding of the operating environment and a meticulous matching of the bearing's material composition to the specific demands of load, speed, temperature, and atmosphere. By applying the systematic selection process outlined in this guide, engineers can harness the unique benefits of solid lubrication to create more reliable, maintenance-free, and environmentally robust mechanical systems, from the depths of industrial processing to the vast expanse of outer space.

SF stands for three-layer composite, namely steel plate layer, copper powder layer and plastic layer. The steel plate layer plays the role of assembly...

See Details

MXB-DX boundary oil-free bearings, equivalent to SF-2 self-lubricating or dry plain bearings, which is based on steel plate, sintered spherical bronze...

See Details

Mining machinery and equipment are very easy to wear during use. In order to extend the service life of the equipment, Mingxu Machinery recommends tha...

See Details

MXB-JTGLW self-lubricating guide rails provide resistance and reduce friction, ensuring extended durability and enhanced performance. This product pro...

See Details

MXB-JGLX self-lubricating guide rails cover multiple properties such as high wear resistance, high temperature resistance, corrosion resistance, etc.,...

See Details

MXB-JSOL self-lubricating guide rail is an L-shaped guide groove type self-lubricating guide rail, which is made of a combination of high-strength bra...

See Details

Constructed from high-grade graphite-copper alloy, the MXB-JSL L-type self-lubricating guide rail is strategically installed at the mold clamping guid...

See Details

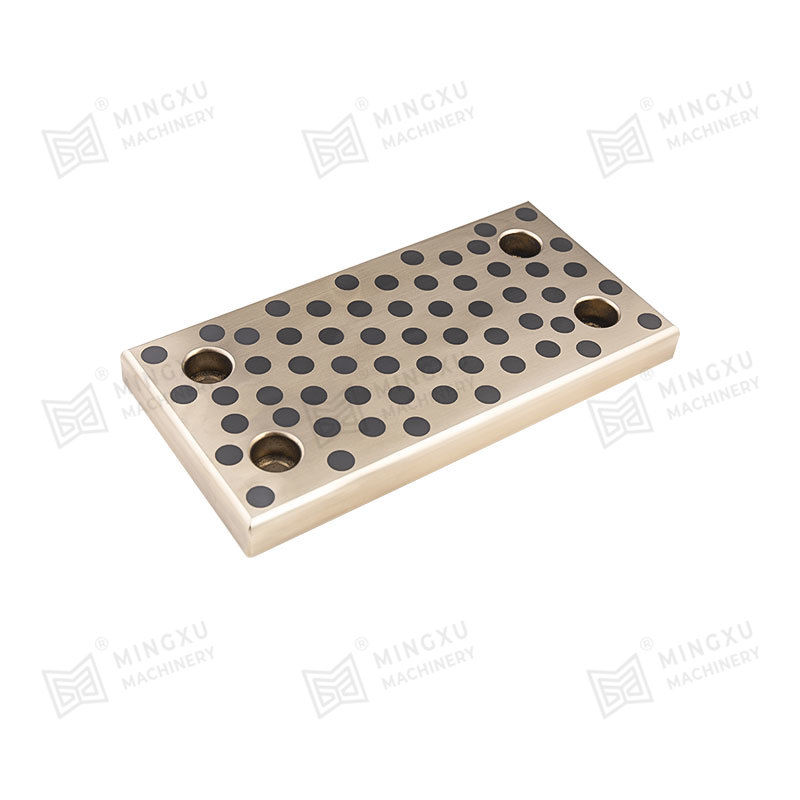

MSEW JIS 20mm Standard Wear Plate is based on high-strength brass, tin bronze, steel-copper bimetal, cast iron or bearing steel. The surface is inlaid...

See Details

MX2000-1 graphite embedded alloy bearing, MX2000-1 graphite scattered alloy bearing is an improved product of JF800 bimetallic bearing. It has the pre...

See Details

The bimetallic slide plate with wear-resistant alloy sintered on three sides is a new type of self-lubricating plate. Compared with the general single...

See Details

Contact Us